by Leo Linbeck III 09/02/2017

[This is a re-post copied directly from New Geography ]

Narratives are not necessarily built on facts; they’re built on stories, pictures, graphics, and videos. Ideally, we want our narratives to be aligned with the facts; but that doesn’t always happen.

Here is a synthesis of some of the predictable narratives being spun in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Harvey from such places as The Washington Post, Slate, The Guardian, Newsweek and NPR:

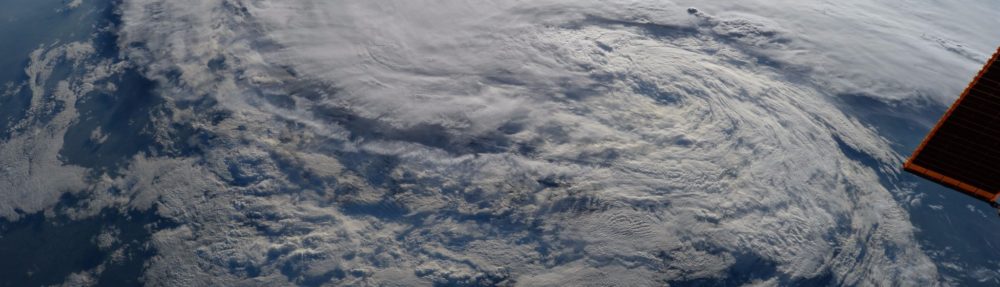

Hurricane Harvey was a catastrophe of epic proportions. Floodwater is everywhere; people can only move around the city using boats and helicopters. Local officials failed to order evacuations, so Houstonians have been forced from their homes as flood waters rose, and the death toll is horrific and rising.

But Houston had it coming. It is a miserably hot swamp where no one really wants to live. It embraced a “wild west” approach to growth, paved over wetlands, and refused to implement zoning, which would have lessened the impact of Harvey by requiring developers to mitigate the impacts of new projects. Moreover, it is the global center of the energy business, which is the biggest driver of climate change – one impact of which is the increased frequency and severity of hurricanes like Harvey.

Look at these pictures of flooded streets; families in boats, or shopping carts, or floating on inflatable mattresses; bridges that are totally submerged, and littered with abandoned cars. Check out these graphics showing how Houston has paved over much of the land, destroying wetlands and creating impermeable barriers and exacerbating the impact of major rainstorms. Read these interviews with experts who bemoan Houston’s lack of centralized planning, and who implore the city leaders in Houston to use their power to address the many failures that became evident during Hurricane Harvey.

These narratives, alas, are a combination of ignorance, and arrogance that tells the reader more about the narrative spinners’ flawed view of Houston than about the city itself.

Let’s start with some facts and perspective:

- Harvey is the wettest storm ever to hit the continental US. Over 50 inches of rainfall and 1 trillion gallons of water fell during the event. No one builds a church for Easter, or a gated community for the zombie apocalypse. It’s pretty naive to expect people to expect the unexpected.

- So far, there have been fewer than 50 storm-related deaths. Each of these deaths is tragic, but even if that number creeps higher, it is a stunning low fatality rate for such a major event in such a large city. The Houston region has more than 6.6 million people, and every year more than 40,000 of them die – so Hurricane Harvey increased the annual death tally by about 0.1%. Sad, but not catastrophic.

- An estimated 30,000 people have been forced from their homes. This is approximately 0.5% of the population of the Houston region. In other words, 99.5% of people in the Houston region have been able to stay in their homes. Unfortunate, but not catastrophic.

- The Trump Administration has estimated that 100,000 homes were damaged or destroyed. While it is unclear how that estimate was obtained – if 30,000 people were forced from their home, then probably 70-90% of those homes did not sustain enough damage to force an evacuation – the Houston region has more than 1.6 million housing units, so about 6% of homes sustained damage of some kind. Lamentable, but not catastrophic.

- Economic impact estimates are all over the map at this point; initial estimates were in the $30-40 billion range, but have been rising since then. Let’s say they end up being comparable to Superstorm Sandy, which caused about $70 billions of damage in today’s dollars. The Houston region GDP is about half a trillion dollars a year, so Harvey’s economic cost would be about 14% of our total economic output. Expensive, but not catastrophic.

A dispassionate weighing of these facts would tell you that while stressful events always help identify areas for improvement, by and large our infrastructure and leadership performed admirably well under extraordinary circumstances.

It other words, the facts would tell you that Harvey was not a catastrophe for Houston; it was our finest hour.

But the narrative spinners have an agenda: they want to assert that this event was an utter failure for Houston, and shame our city and county leadership into embracing centralized planning, and ultimately zoning. They believe in a top-down, expert-driven technocracy that rewards current real estate owners by actions that restrict new supply, raise property value (and therefore taxes), stifle opportunity and undermine human agency. As a life-long Houstonian, I would like to politely ask the narrative spinners to please pound sand.

Peter Drucker once said that culture eats strategy for breakfast, and Houston’s culture is one of opportunity. People come to this city to build a better life for themselves, to start and raise a family, and to do so with the support and encouragement of neighbors. This culture of opportunity means that Houstonians welcome newcomers, in a way that older or more status-conscious cities do not. Houston may not be a nice place to visit during the summer, but it is a great place to create a life all year round.

This culture really shines through during events like Hurricane Harvey. Despite what the narrative spinners would have you believe, we are not rugged individualists; we are rugged communitarians. We know that when times are tough, you must rely first on family, then friends, then neighbors, and then – and only if you’re one of the few, unfortunate folks who cannot rely on any of those three – on the government. And if we have family, friends, or neighbors who can help, reaching out for government support is actually taking resources away from those who need them more.

In short, the best governance to rely upon is self- governance.

When the storm hit, I saw these networks in action. People first took care of family – in my case, my five siblings and I were in regular communication, checking in on how each of us was weathering the storm. Good news: everyone came through pretty much unscathed.

Once it was clear that my family was OK, my wife and I began to focus on neighbors and friends. Yesterday, I spent several hours with neighbors clearing away trees that had fallen across streets in our neighborhood, making them unpassable. It was hard work – lots of chain sawing and branch hauling – and we were helped by a crew that was distributing power poles in our area. But folks just driving in the area would also stop and help, doing what they could, or just providing fellowship and encouragement.

One lady in the neighborhood brought us some chicken meatballs for lunch – no one asked her to do that, she just wanted to help however she could. (The meatballs were delicious – thanks Costco!)

Also, in our network of friends, there were a couple of families who were forced from their home. We worked together to find them places to stay, and today a group of about 40 men, women, and children went to their house today to box up and move out their valuables, throw away everything else, and tear out the damaged drywall. People brought tools, gloves, and a can-do attitude, and a job that might have taken weeks was finished in about 6 hours. Our friends now have their valuables with them in a rented home (found by another friend in our network), ready for the next step in returning to normalcy.

These stories are real, and not about heroes doing the unusual. They are commonplace and just the way things get done in Houston. If you have friends in Houston, just ask they will tell you similar stories.

Of course, leadership is important, and our regional leadership did great. Mayor Sylvester Turner and Judge Ed Emmett were both calm, deliberate, and stayed on task throughout the crisis. Governor Abbott and President Trump did their parts, but make no mistake about it – this was a local challenge that required top-notch response from local officials. And they did their jobs well.

Houston was able to absorb the wettest storm on record with remarkably little loss of life and property also because of good engineering, informed by the experience of previous storms. A good engineer designs systems that won’t fail when hit with an expected event; a great engineer designs systems that fail gracefully and non-catastrophically when hit with an unexpected event. Hats off to our great engineers.

However, a focus on Houston’s public officials or public infrastructure will lead you away from the more important truth: our response was driven by thousands of Houstonians who voluntarily stepped up to the challenge, and didn’t wait for some central authority to tell us what to do. The truth is that Houston’s culture was its biggest asset, a culture of mutual support that is extraordinary in a city of this size and diversity.

And this culture is not an accident; it the consequence of a system that was designed to be driven from the bottom-up, by regular folks, responding to needs on the ground rather than some kind of theoretical plan put together by experts with no stake in our future, or interest in our family, friends, or neighbors.

Of course, there is always room for improvement. By studying what happened, we will find ways to improve the system for the next storm – and there will always be a next storm. We learned a lot from Ike, Rita, and earlier storms. When I was a child, a couple of inches of rain would flood my neighborhood; today, that same neighborhood absorbed 25 inches of rain and made it through. We have come a long way.

Harvey was a difficult challenge, but not a catastrophe. However, it would be catastrophic for city leaders to accept the narrative spinners’ version of what happened in Houston. It is demonstrably wrong on all counts:

- Houston is a miserably hot swamp where no one really wants to live.

It’s hot during the summer, but it is pleasant the rest of the year. As this map shows, Houston actually gets more “pleasant days” than Miami, Raleigh-Durham, Chicago, Portland, or Phoenix. Forget your preconceptions for a moment, and answer a simple question: how could a place get to a population of 6.6 million if no one wanted to live there?

- It embraced a “wild west” approach to growth.

Houston’s approach is not the “wild west.” We have land use that is managed from the bottom up, through a system of deed restrictions that often include local homeowners’ associations to police those restrictions. What we don’t have is a top-down, expert-driven, bureaucratic system of centralized planning. As a result, it’s easier to develop real estate than most cities, which keeps real estate prices – especially housing prices – low relative to the rest of the country. It is actually a more sophisticated and economically efficient system than the antiquated politically-driven zoning system that generally favors entrenched interests over new entrants.

Over an 18 year period, Houston lost about 25,000 acres of wetlands. But this amounts to about 4 billion gallons of storm water detention capacity. As stated above, Harvey dumped about 1 trillion gallons; so the lost capacity represents about of 0.4% of Harvey’s deluge. But it’s also important to understand that the streets – a huge portion of the paved area – are used as detention, places to hold storm water temporarily when there is nowhere for it to drain. Houston’s strategy for many years has been to use streets as detention and runoff channels, the idea being that it is better to flood a street than a house. And the city’s performance under Harvey confirms the wisdom of that strategy.

- Refused to implement zoning, which would have lessened the impact of Harvey by requiring developers to mitigate the impacts of new projects.

This is the most ridiculous of all the claims made by the narrative spinners. Mayor Turner put it best: “Zoning wouldn’t have changed anything. We would have been a city with zoning that flooded.” Proof positive of this fact: one of the harder hit areas was Sugar Land, just south of Houston. Sugar Land has zoning. Alas, Harvey was unaware of that fact and dropped 30+ inches on them anyway (and they handled it well, just like the City of Houston, evidence that zoning was not correlated with impact).

- Moreover, it is the global center of the energy business, which is the biggest driver of climate change – one impact of which is the increased frequency and severity of hurricanes like Harvey.

Yes, Houston is the center of the energy business. But Houston’s energy industry is as much about natural gas as crude oil, and the increasing use of gas in power generation has led to a much-improved carbon dioxide picture in the US. If you believe that CO2 is causing climate change, you should be thanking the energy entrepreneurs in Houston for bringing cheap, clean natural gas to the nation. Moreover, the hypothesis that greenhouse gas emissions impact Atlantic hurricane activity is controversial; an official NOAA publication stated that “neither our model…nor our analyses…support the notion that greenhouse gas-induced warming leads to large increases in either tropical storm or overall hurricane numbers in the Atlantic.”

A final point about who pays for all this.

The narrative spinners have made a big deal about how federal funds will be needed to rebuild Houston, and therefore Houston must do what they say.

My take on this is: we are going to rebuild with or without you, so you are not the boss of us.

Most of the money from previous Texas hurricanes has come from private insurance. And, in some ways, this process of rebuilding restores a balance in the economy. For the past couple of decades, almost all homeowners have paid for insurance but few people make a claim. Most of that money sits on the balance sheet of big insurance companies to pay out future claims, and those companies often invest those dollars on Wall Street and real estate. That’s all fine – good, healthy commerce.

Now the time has come for the flow to go the other way. Big insurance companies will be paying out money to settle insurance claims, and most of that will go to working class Americans who will rebuild damaged property. Demand for labor will rise, as will wages, as the money starts to flow. The tilting of the economy away from physical labor toward the financial sector will reverse – maybe only temporarily, but it will still reverse.

Of course, if the federal government decides to give away money, I suppose people will sign up for it. But this madness eventually needs to end. The federal government is broke, and insisting that folks in Kansas or Vermont pay for a hurricane in Houston is silly on the face of it. This is not an invading army we’re talking about here. It’s a really bad storm. The Constitution doesn’t contain the words “storm,” “weather,” or “insurance.” Why are we continuing to twist its meaning to make Congress and the President look like heroes? If they want to help, let them help with their own time, talent, and treasure. Like the rest of us.

But we also don’t want to be suckers. If Washington DC decides not to help Houston, they should end it for everyone in the future. Which they should, in my opinion.

Bottom line: I believe we should celebrate the ability of the nation’s fourth largest city to absorb the wettest storm on record and bounce back with gusto. It is a testament to the culture of my hometown and the leadership that supports and nurtures that culture.

Now, if you will excuse me, I have to get back to work. That wet drywall won’t remove itself.

Leo Linbeck III is a husband, father of 5, CEO of Aquinas Companies, Executive Chairman of Linbeck Group, a Houston-based institutional construction firm, Founder and Chairman of Fannin Innovation Studio, a biomedical startup studio, and Lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business. He was also the Founding Chairman, and is currently the Vice Chairman, of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism, a Houston-based think tank.

The regular meeting agenda has one noteworthy item; The County Engineer seeks authorization to hold a “workshop to discuss regulatory changes needed to the flood plain management and infrastructure regulations in response to Hurricane Harvey.”

The regular meeting agenda has one noteworthy item; The County Engineer seeks authorization to hold a “workshop to discuss regulatory changes needed to the flood plain management and infrastructure regulations in response to Hurricane Harvey.”

“Nothing bad happened today” is not a story that will sell very well. Stories about public infrastructure systems that work the vast majority of the time do not sell newspapers or generate online clicks.

“Nothing bad happened today” is not a story that will sell very well. Stories about public infrastructure systems that work the vast majority of the time do not sell newspapers or generate online clicks.